If I had a dollar for every article written about the shock value of Tracey Emin’s work, I probably wouldn’t have had to transfer money out of my savings account for a coffee to pull myself through today. I can’t promise you a new, scintillating take on Emin’s work, nor an intimate interview with her, but I can tell you that standing in front of My Bed felt like getting into bed with a stranger, a lover, a friend, and a mirror all at once.

The first time I saw My Bed, I was seventeen years old, on the cusp of adolescence, about to graduate high school and move to Los Angeles. As I write about My Bed today, I’m twenty-one, on the cusp of adulthood, freshly graduated from college and getting ready to move to London, where I first saw the piece.

Around the corner from where I lived for six months earlier last year, Emin lived and worked in East London in the late 1980s-1990s as a member of a group called the Young British Artists, alongside artists like Sarah Lucas and Damien Hirst. In 1993, she and Sarah Lucas opened a storefront on January 2nd in Bethnal Green, where they exhibited work and sold everything from tee shirts to ashtrays to pins to papier-mâché sex toys. Chainsmokers, Lucas and Emin would sign cigarette packets and sell them for £3.10, the price of their next pack.

Since the beginning, Emin and her work have been controversial. In 1997, she appeared drunk on a live British television talk program and swore belligerently before walking off the stage, mic still attached. Much of her work is similarly crude, with titles like Fucking Down An Ally and Get Ready for the Fuck of Your Life. Two particularly humorous pieces formed from neon lights were Is Anal Sex Legal, which was complemented by Is Legal Sex Anal. One can imagine that the highbrow British art world, along with the ever-ruthless tabloids, had an abundance of criticism for Emin and her art.

Emin’s work has long contested the patriarchal pedestal that “high art” has its roots in. In a piece entitled Everyone I’ve Ever Slept With (1963- 1995), Emin appliquéd the names of – you guessed it – every person she’s ever slept with, both sexually and innocently, on the inside of a tent. Through working with similarly “domestic” art forms like needlework and textiles, Emin flips the misogyny of the art world on its head. The Guardian journalist Liz Hoggard said, “I love her wanting to have [that] dialogue with older, male artists. When she burst on the scene, along with Sarah Lucas, she made the handmade cool again. Suddenly, it was okay to work with the domestic – embroidery, fruit and veg, cigarettes, dirty sheets.”

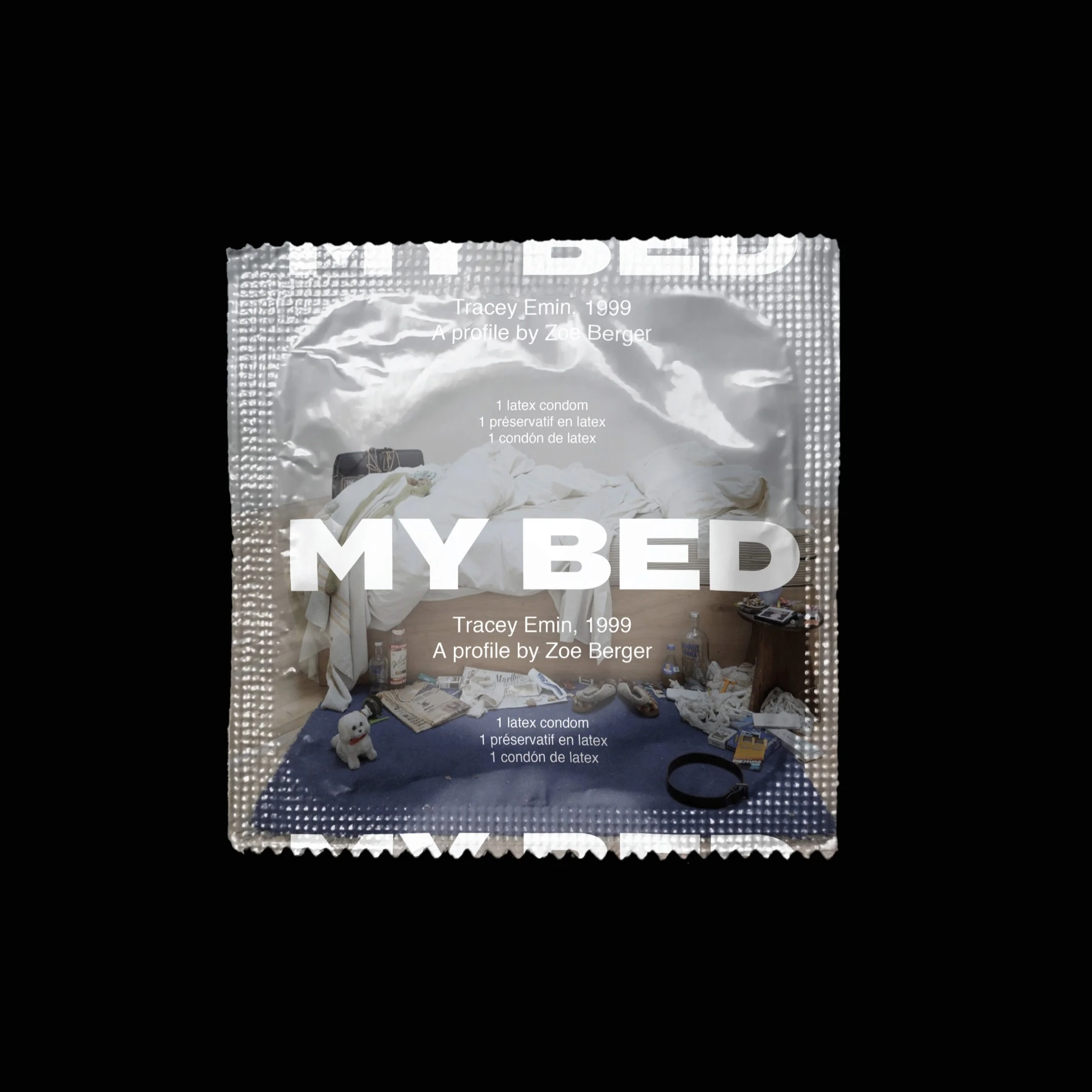

My Bed is littered with suicidal, self- destructive, and addictive imagery: a belt lies buckled on the floor, a razor rests upturned amongst dirty napkins, empty liquor bottles lean against the bed frame with their caps missing, cigarette butts lie cold on the nightstand, used condoms blend in with dirty bedsheets.

Looking at these photos now, I remember what it felt like to hold a belt to my neck, to gaze at the razor on the edge of the tub during showers, to wake up in a bed littered with tissues. I remember seeing my profile in the film from my first Polaroid. I remember what it felt like to hold a moment in my hands.

And now, I remember what it felt like to get into bed with a moment, Tracey’s moment.

Emin wiped away tears reinstalling the piece at the Tate. She explained that getting under the bedsheets to create the ravaged, rumpled effect of the original installation suffocated her in a way that only the past version of herself could. The sheets had stiffened over time, forcing her to work herself into the piece all over again. She describes how every reinstallation of My Bed pulls her further from her past self in an interview with The Guardian:

“It gets older, and I get older, and all the objects and the bed get further and further away from me, from how I am now... the belt used to fit around my waist and now it actually fits around my thigh. So that gives you an idea about how much things change.”

Today, I doubt the piece would be anything more than a blip in the radar of the contemporary art world, in terms of its shock value. The Chapman brothers, Milo Moiré, Maurizio Cattelan, and other later controversial artists make My Bed look tame. Through the eyes of art historians, the time-capsule that the bed protects dates the piece. Emotionally, however, My Bed will always be timeless. My daughter may see Emin’s work one day and connect in the same way I have. Even though the artwork is now considered “quaint”, it is still just as resonant as it would be if that was your miserable bed you had just climbed out of.

The time that has passed between its inception and reinstallation make the piece now suffocating to Emin in the way that her separation is an act of shedding off skin. Seeing My Bed at seventeen in the same mental space that she was in, almost twenty years after she had left it, left a nostalgic taste on my tongue, as if I was a weird reincarnation of the skin she used to live in.

Writing of My Bed at twenty-one now is less reminiscent of the actual experience of depression as it is a window of memory into this thing she had left behind that I was still stuck in.

I recognize I am just another naïeve barely-adult that thinks she’s special for liking art, and the last thing I want to be seen as is presumptuous, but I can’t help but feel a connection to Tracey and My Bed that feels doubled (or tripled, I guess) because of a few things.

My mother was born the same year as Tracey. I was born the same year My Bed debuted. She moved into “The Shop” with Sarah Lucas on my birthday. Numerical concurrence isn’t that rare, and these aren’t the craziest of coincidences, but at the end of the day, the feeling isn’t about these chance similarities. It’s about real things she went through, and that I went through, and that other young girls probably have and will always go through.

Looking at my own bed, I feel as if I’m sleeping with all the past versions of myself. I’ve slept, fucked, cried, vomited, pissed with laughter, wanted to die and wanted to live in this bed.

The second she got out of the bed, four days after she got in, she saw the piece in a gallery, surrounded by white space, out in the world. “I saw myself out of that environment, and I saw a way for my future that wasn’t a failure, that wasn’t desperate. One that wasn’t suicidal, that wasn’t losing, that wasn’t alcoholic, anorexic, unloved.”

I see it too.